Today’s at History in the Kitchen we took a look at three documents, the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration of Sentiments, and Frederick Douglass’s speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Similar to a lesson I teach in the classroom, I think it is vitally important to reiterate the ideals of the Declaration of Independence are, for some groups of people, far from the reality and Independence, even today, can be viewed from man different lenses.

The Declaration of Independence has three parts: the preamble, the grievances, and the actual part that declares independence. The preamble tells the reader how the government should treat the people. Based on the philosophy of John Locke, it is based on a social contract. The government gets its power from the people only if it protects their natural rights of life, liberty, and happiness. If the government fails to protect the peoples’ rights, the people have the duty to take the power away from the government. In the second part, the grievances, Jefferson, et. al list 27 reasons why the United States is declaring independence. Its basically all of the things that King George did wrong (really… Parliament played a heavy hand, but they didn’t want to indict Parliament.) The last paragraph tells the King that the U.S. is permanently severing ties with him and Great Britain. In the words of T-Swift, they are never ever, ever, ever getting back together. Ever.

The Declaration tells us that “all men are created equal,” but that wasn’t exactly true. It wasn’t “all” men. There’s evidence of this right in the document itself. The 27th grievance, “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions,” seeks to incite prejudices against Native Americans already held by many colonists. It is obvious from that line alone that the Native Peoples of North America were not meant to be included in that promised equality. The second issue with the original document is what it left out. Jefferson wrote a grievance pinning the slave trade on King George and blaming him for the spread of slavery in the colonies, which Jefferson calls “execrable commerce.” This clause, which admitted that slavery was a great sin, was taken out of the final draft. Again, not everyone was included in “all men.”

Immediately upon the publication of the document, however, the people who were not considered equal noticed. Slavery was still legal on July 2, 1776 and continued to be legal until December 1865. The spirit of slavery still exists to day in the form of systemic racism. Women were considered “legally dead”– women didn’t have the right to vote, didn’t have the right to hold government offices, didn’t have the right to property or their own money– the list goes on.

In July 1848, three hundred men and women met in Seneca Falls New York. They met to discuss women’s rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton read the “Declaration of Sentiments” at this meeting in which she called upon the federal government to give moral, economic, and political equality to women. The Declaration of Sentiments calls upon the Declaration of Independence. Cady Stanton used the same structure- a preamble, grievances, and a declaration- to call for women’s rights. She says, “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal.” She tells the reader about how the government SHOULD treat women and then she lists how the government and society ACTUALLY treat women. It ends with a promise to work tirelessly for what is “right and true.” The people at the Seneca Falls Convention recognized the inequality in our nation and called upon our founding document in working to fix it. Read the entire document here.

On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglas gave the keynote address “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” at an Independence Day celebration in Rochester, New York. He addressed an audience made up of primarily white women by highlighting the hypocrisy of the ideals of the Founding Fathers with slavery. He asks questions about what the Declaration of Independence and Independence day meant to Black Americans who were still experiencing slavery. He says, “I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice are not enjoyed in common.” While he praises the Founders for their ideals, he very clearly tells the people to whom he is speaking that the equality and natural rights that the Declaration promises did not apply to Black Americans. View the entire document here.

Douglass ends with talking about hope, “I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope. While drawing encouragement from “the Declaration of Independence,” the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age. Frederick Douglass knew that the fight against slavery was far from over, just as we know the fight for justice and equality for many different Americans- Black Americans, women, and immigrants to name a few- is far from over today. However, the Declaration can be celebrated as a document of hope for our future. The tenacity of the American people for fairness and equality is unmatched. That alone is cause for optimism.

Recipe

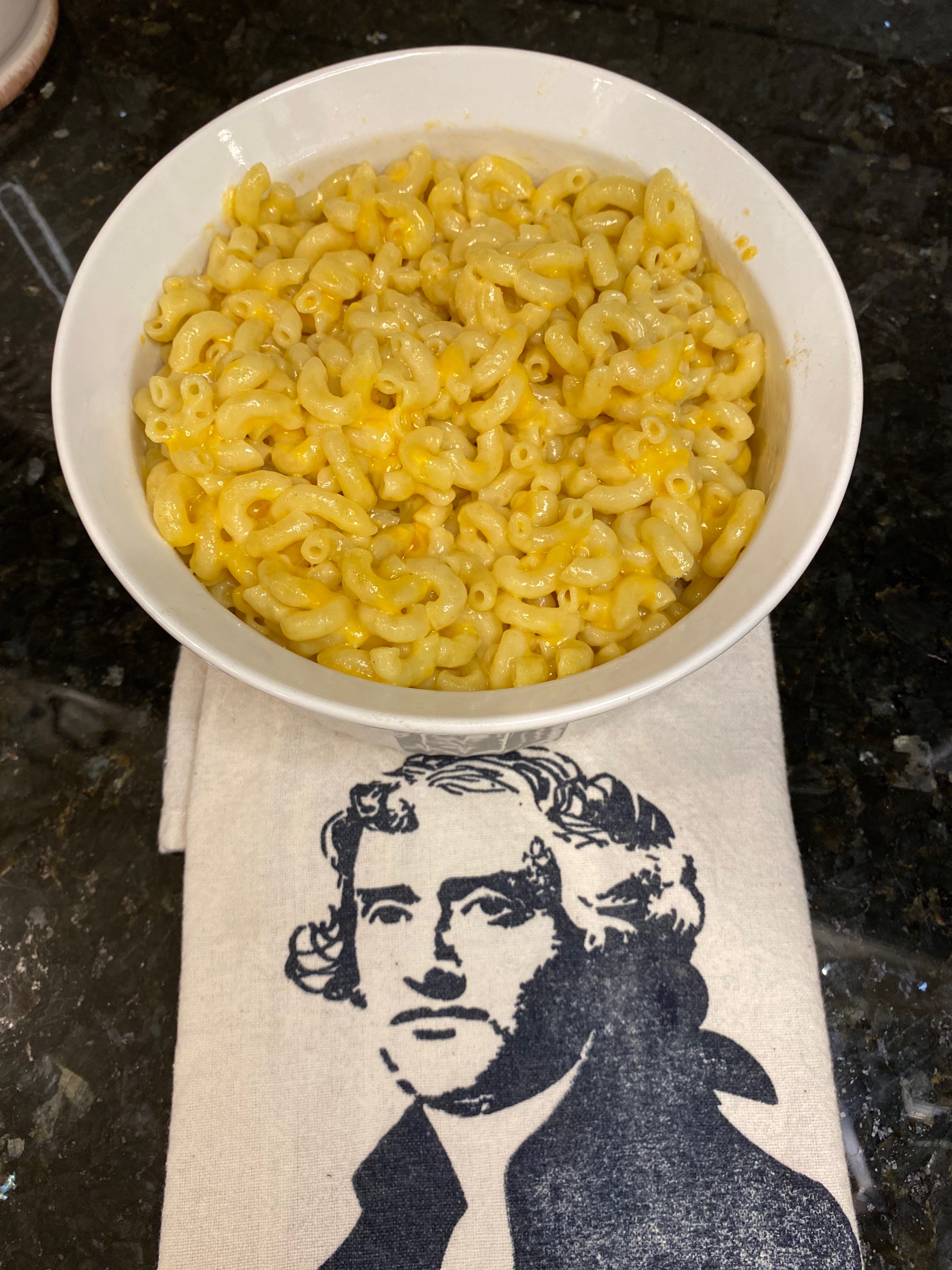

Thomas Jefferson’s Mac & Cheese (Remember, Jefferson would not have cooked this! Enslaved people cooked it for him).

Ingredients:

-1c shredded sharp cheddar

-1/4c shredded parmesan

-1 stick butter

-2c small, tube macaroni

-salt

Process:

- Preheat the oven to 350.

- Boil salted water, cook macaroni for about 10 minutes or until very tender.

- While the macaroni is cooking, mix the cheeses and the butter together well.

- Mix cheese mixture into macaroni and put in a greased baking dish.

- Bake macaroni mixture for 10 minutes or until cheese melts.

- Enjoy!