You know that game of telephone where the person at the head of the line whispers a word or phrase into the next person’s ear and the message has to be passed along, unchanged, through an entire line of people? That’s how I view textbooks in the study of history While there are solid textbooks that offer students and teachers acceptable interpretations of history, many offer a watered-down interpretation of the past at best or a muddled, inaccurate and/or uninclusive interpretation at worst. It is important to teach our middle school historians (and future voters!) how to interpret events based upon primary sources, or from source material that is from the era they are studying if we want to create analytical thinkers. If we truly want to make our classrooms a place where history is something to “do,” like students “do math” and “do science,” then we have to take note of what the teachers in other disciplines are doing and use those methods, such as observation and interpretation of fact. Cue primary sources.

You may argue that primary sources are biased, particularly the written ones, but there is something that students can learn from that bias, as well. By viewing multiple primary sources that give students a view of the world through the lenses of several different people about the same event, they can draw their own conclusions about the era.

Digesting primary source documents can be difficult for middle school students. As much as possible (except for maybe Magna Carta!) I give them the source without editing it for style or language. Observing how human communication changes over time is part of the experience when using primary source documents. However, I do provide some scaffolding in order to assist students in reading what can be a challenging concept to understand or difficult language to grasp. They are learners and we can’t expect them to be able to read and interpret documents without some assistance.

- Most often, I will provide context for the documents given. That might include talking to them about the document prior to their working with it or writing an italicized paragraph explaining the context of the document on the top of the page. Either way, students need to understand where in time they are and who is writing.

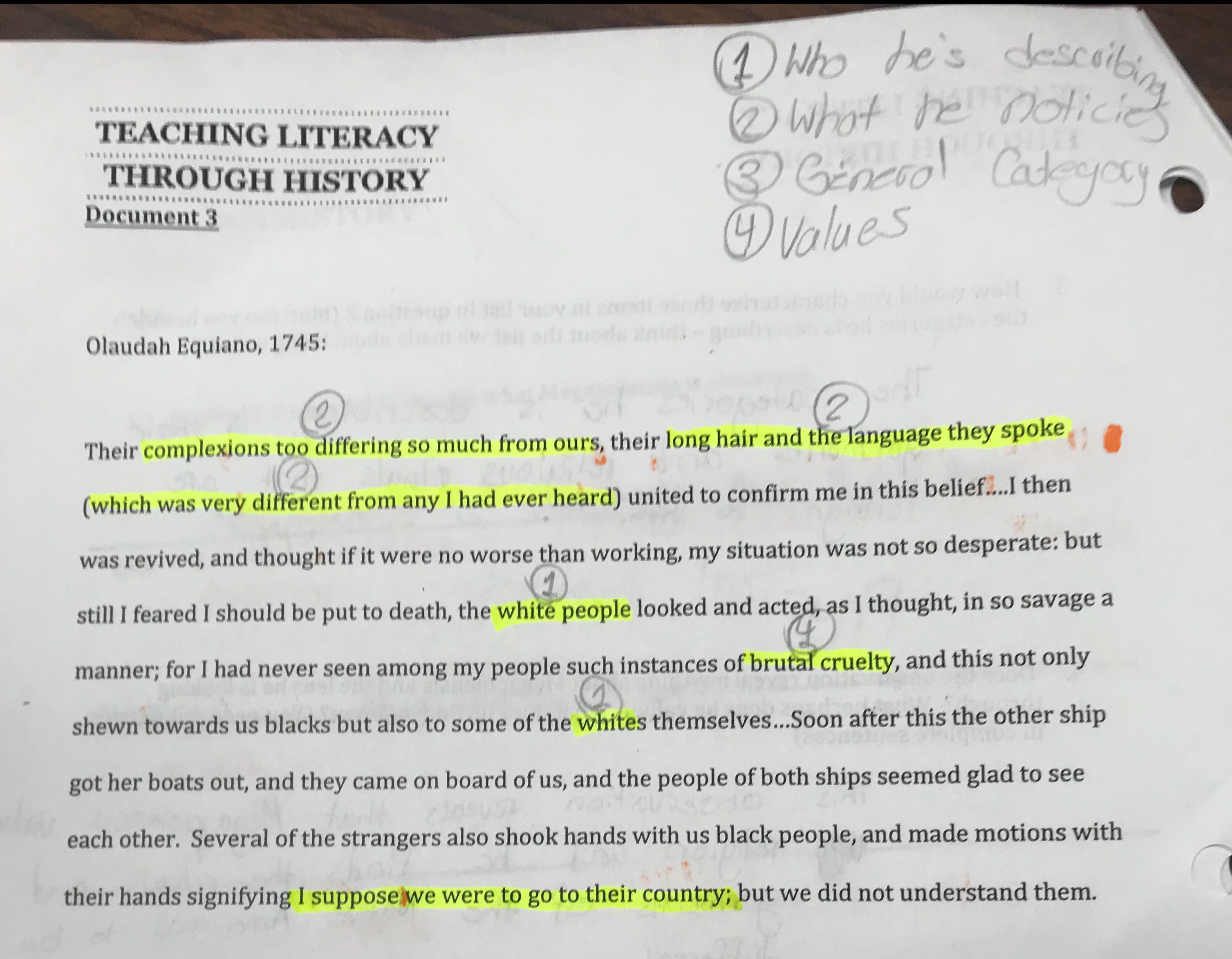

- Provide questions to guide student annotations. Start simple. Ask students to identify main ideas of the texts and make lists. For example, in a lesson developed by my colleague, students read an excerpt of Johannes Megapolensis’ writing in which he describes his first contact with Native Americans in the New World. My colleague asked students to identify the descriptors Megapolensis uses, then asks students to categorize those descriptors (appearance, religion, resources, etc.), and then lastly asks students to use higher-order thinking skills to make inferences about the lens through which Megapolensis saw them. A couple of my students annotated by categorizing with a numerical or color system according to the questions they used to guide their reading (see picture below). This helped them digest the material.

3. Model: And I don’t mean strut your stuff; I mean SHOW THEM. Put the source up on the whiteboard or the smart board or whatever it is that you have to display things for students and literally do the work in front of them and outline your process.

4. Let them practice, preferably with you in the room. Allow them to ask you questions, trip up, make mistakes, and try again. Give them a safe space to try so that the document you’re asking them to analyze is less intimidating. The more comfortable they are, the more they’ll be willing to try.

Just as much as it is a scientist’s job to draw conclusions from evidence, it is an historian’s job to use the evidence available from the time period being studied to piece together the whole story of an era. While some pieces may be missing, we are doing our students a huge disservice if we don’t teach them how to dissect and analyze evidence to draw a conclusion.

Need help finding primary source documents for your students to practice their skills?

- Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History: I always start at Gilder Lehrman. GLI has an exhaustive online collection of American history primary sources plus lesson plans to use in order to integrate them seamlessly into the curriculum. www.gilderlehrman.org

- National Archives: The U.S. National Archives offers thousands of online documents that can be used in your classroom. They, too, have lesson plans for many documents. www.archives.gov

- Smithsonian Learning Lab: This source is fairly new to me, but a simple search brought up many documents and artifacts that could be used for practicing close reading skills as well as teaching difficult concepts. http://learninglab.si.edu